Thuistezien 291 — 01.01.2022

Lee Kit

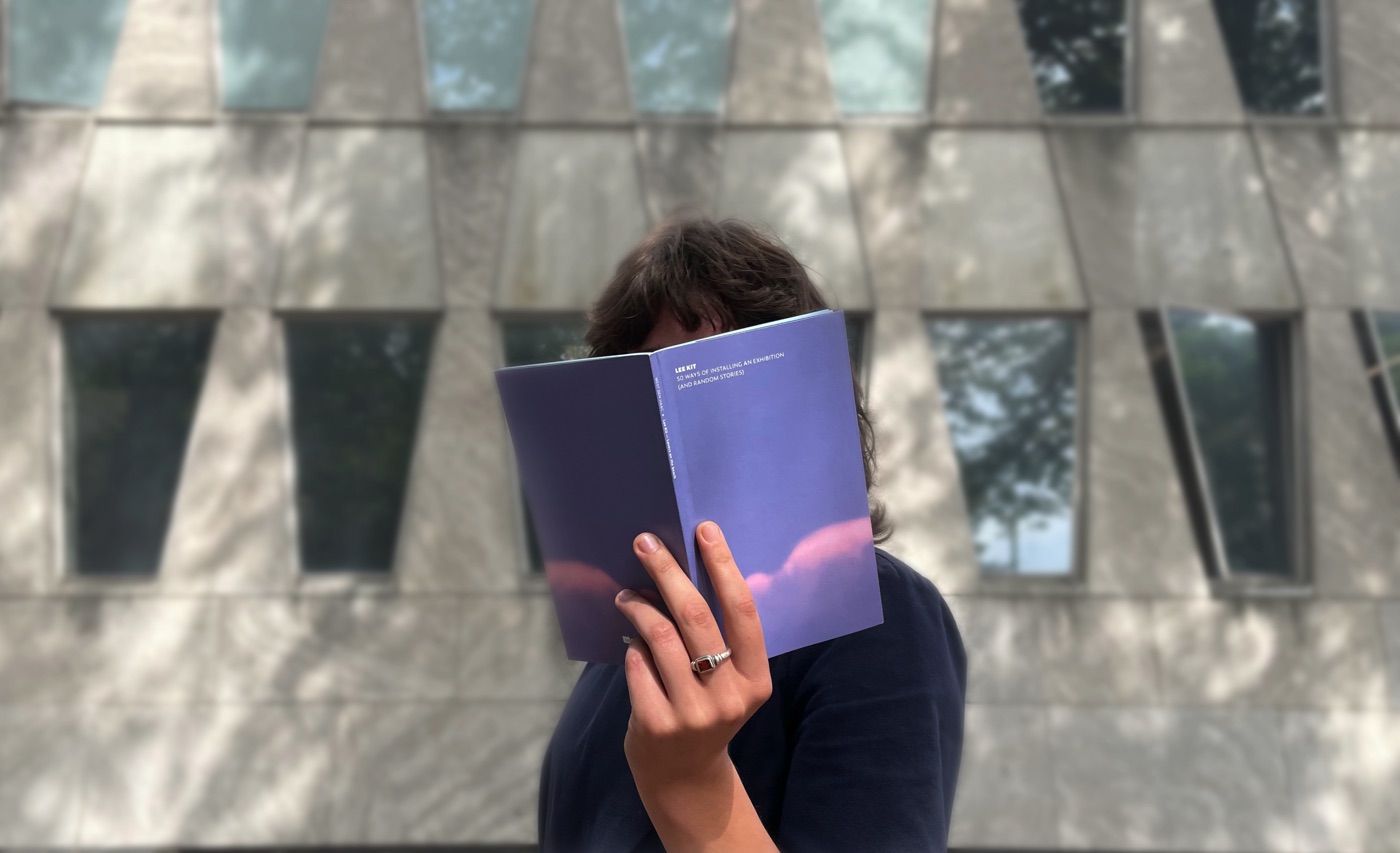

50 Ways of Installing an Exhibition (and Random Stories)

50 Ways of Installing an Exhibition (and Random Stories)

Lee Kit is an artist from Hong Kong, trained in traditional painting, but working with installations and new media such as video and sound. He doesn’t want to call himself a political artist explicitly, though he does acknowledge that his background and political situation is inevitably an influence on his work. His work in the exhibition ‘Lovers on the Beach’ seems to evoke a sweet, yet treacherous daydream; you step into a kind of bubble filled with Twin Peaks-like soundtracks, projections of random images, and shadows while you walk through them, and the light of one of the beamers, positioned on piled plastic storage boxes, shining straight into your eyes. You find yourself in a fever dream, while starry eyed and lost you are blinded, like a deer in the headlights.

Lee Kit seems to want to pull me away from everyday (political!) life, and place me in another, one meticulously designed with a gentle hand. I would like to call it a politics of vulnerability. Emotions are important to him, as well as the feeling of homeliness. His emphasis on the domestic admittedly exceeds the realistic everyday experience, and points towards the vulnerable, accidental moment, and magnifies this to the point of discomfort. Reviews describe on the one hand how he ‘bridges the gap between art and life’, while on the other hand he gets connected to the ‘anti-art’ genre. His bleached tea cloths, an everyday utility as well as an art object, were used as banners during protests in Hong Kong. vApparently the everyday is not art, or even anti-art, until it gets a frame, and in the case of the exhibition, a room. Empty rooms are used to create a space where the fragile moment can be captured. A similar thing happens in the publication ‘50 Ways of Installing an Exhibition (and Random Stories)’, published as part of the exhibition, though not about the exhibition itself. It offers a look inside the mind of the artist, along this fever dream. In this case there are no empty rooms, but empty space is used in a two-dimensional sense. One instruction makes up for a whole page, and can be very short and ostensibly useless (‘Take smoke break’). The physical copy might raise some eyebrows and questions about the value of printed paper. Yet here, the conventional use of empty space, and the magnification of it, becomes relevant in more ways than just 2D. What expectations do we hold towards art and ‘space’ (living space, exhibition space, space on a piece of paper etc.)? Is the publication even about how to install an exhibition?

There is an undertone of irony and cynicism that, to me, comes across as equally political, but it can also be seen as lighthearted humour. Lee Kit makes ‘the heavy’, i.e. deep feelings, drives, critique, more accessible by setting it in a hazy daydream: a smashed up fridge, karaoke, and an instruction manual. Again, a politics of vulnerability.

The exhibition ’Lovers on the Beach’ by Lee Kit will reopen after the lockdown. The publication can be downloaded as a PDF.

Text: Yael Keijzer

Lee Kit seems to want to pull me away from everyday (political!) life, and place me in another, one meticulously designed with a gentle hand. I would like to call it a politics of vulnerability. Emotions are important to him, as well as the feeling of homeliness. His emphasis on the domestic admittedly exceeds the realistic everyday experience, and points towards the vulnerable, accidental moment, and magnifies this to the point of discomfort. Reviews describe on the one hand how he ‘bridges the gap between art and life’, while on the other hand he gets connected to the ‘anti-art’ genre. His bleached tea cloths, an everyday utility as well as an art object, were used as banners during protests in Hong Kong. vApparently the everyday is not art, or even anti-art, until it gets a frame, and in the case of the exhibition, a room. Empty rooms are used to create a space where the fragile moment can be captured. A similar thing happens in the publication ‘50 Ways of Installing an Exhibition (and Random Stories)’, published as part of the exhibition, though not about the exhibition itself. It offers a look inside the mind of the artist, along this fever dream. In this case there are no empty rooms, but empty space is used in a two-dimensional sense. One instruction makes up for a whole page, and can be very short and ostensibly useless (‘Take smoke break’). The physical copy might raise some eyebrows and questions about the value of printed paper. Yet here, the conventional use of empty space, and the magnification of it, becomes relevant in more ways than just 2D. What expectations do we hold towards art and ‘space’ (living space, exhibition space, space on a piece of paper etc.)? Is the publication even about how to install an exhibition?

There is an undertone of irony and cynicism that, to me, comes across as equally political, but it can also be seen as lighthearted humour. Lee Kit makes ‘the heavy’, i.e. deep feelings, drives, critique, more accessible by setting it in a hazy daydream: a smashed up fridge, karaoke, and an instruction manual. Again, a politics of vulnerability.

The exhibition ’Lovers on the Beach’ by Lee Kit will reopen after the lockdown. The publication can be downloaded as a PDF.

Text: Yael Keijzer

previous

previous next

next