Thuistezien 217 — 27.03.2021

Shapes for Sounds

Timothy Donaldson

Timothy Donaldson

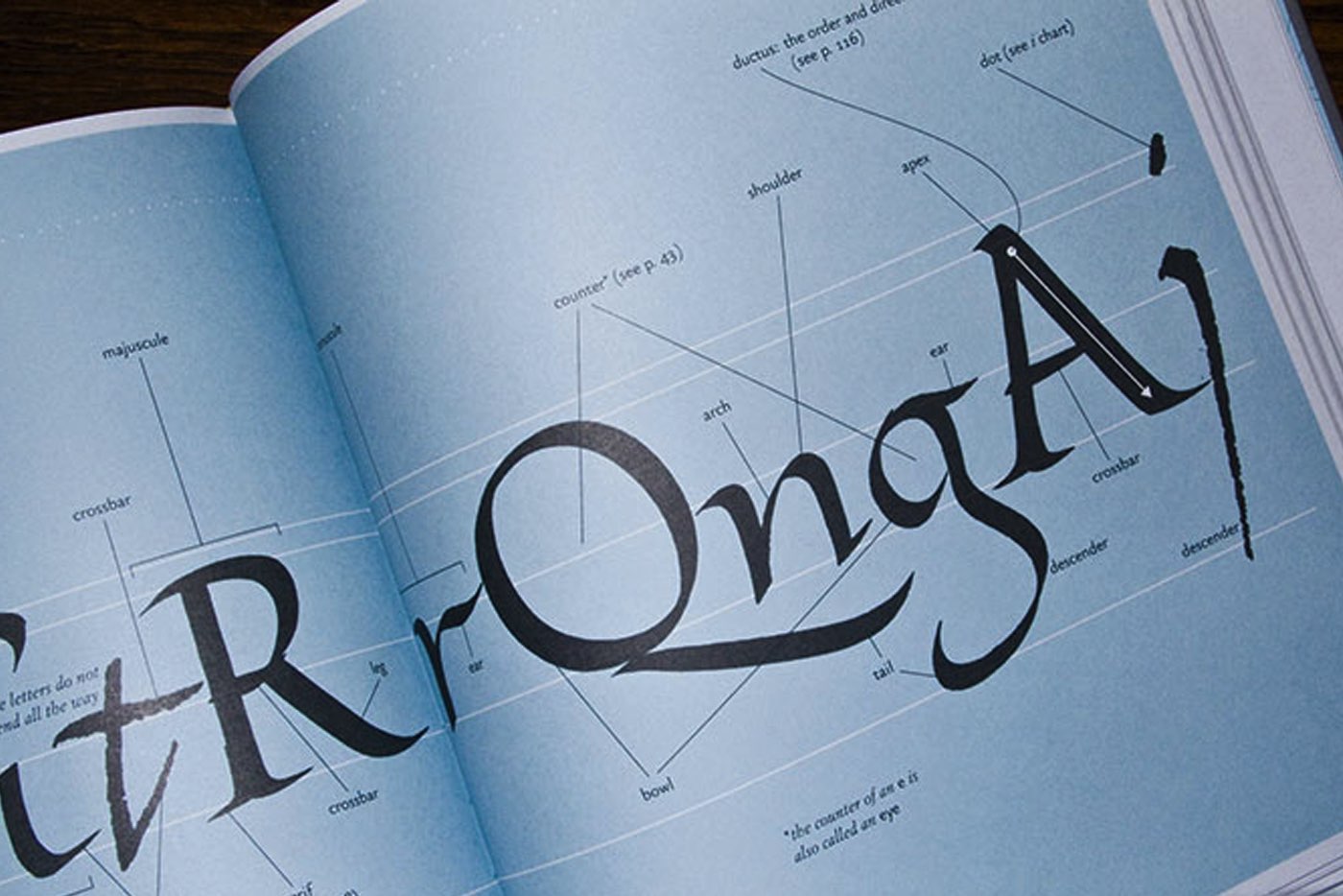

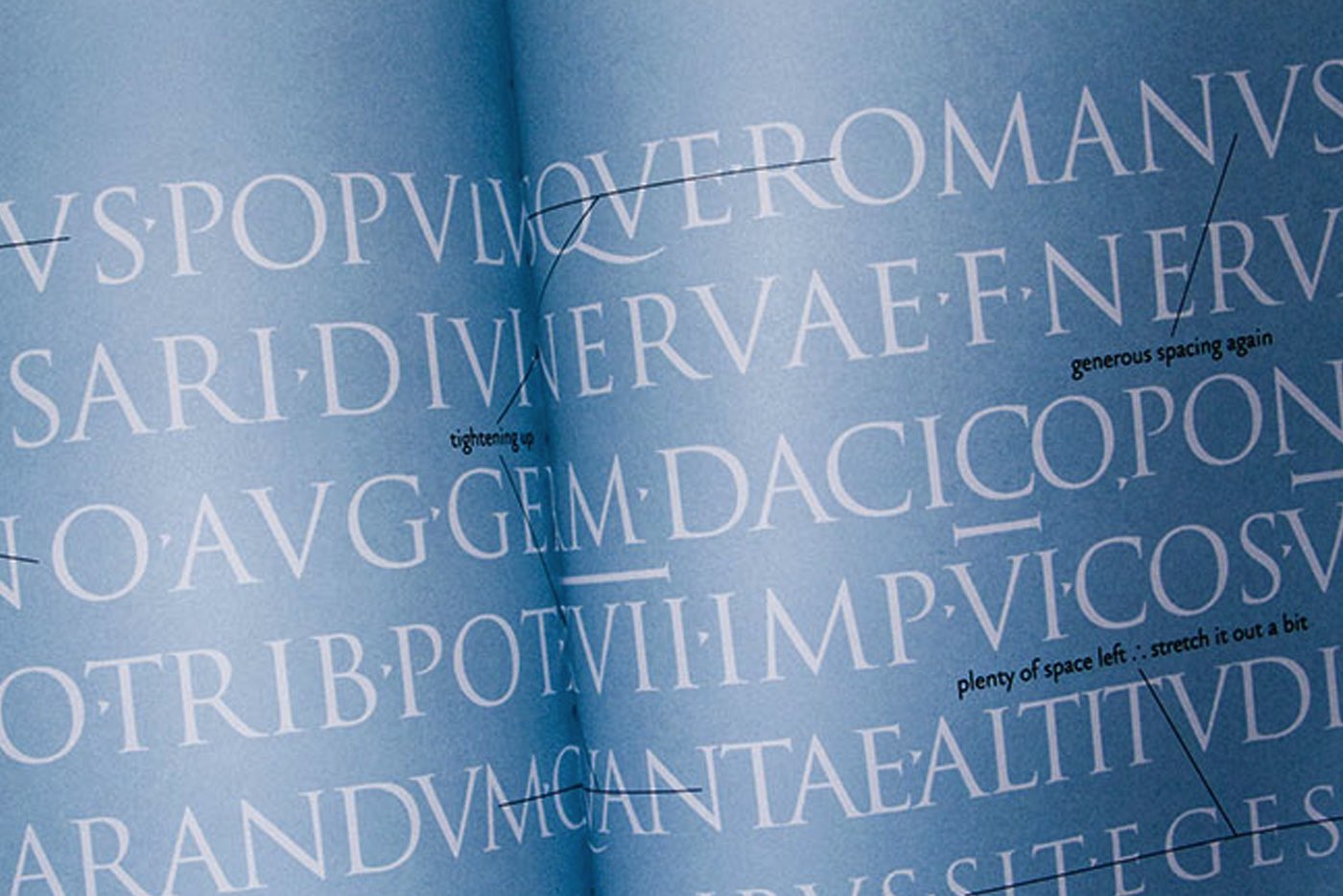

The evolution of the Latin alphabet is complex and comprehensive. Not only in relation with the historical development of each character but also with regard to the sound sign link. With the focus of the typographer, ‘letterworker’ Timothy Donaldson, examines the advent of the Latin alphabet. He illustrates how letters evolved from spoken language to its current written form. Without alphabets, mass communication technology would not exist and this text could not be read or watched at home.

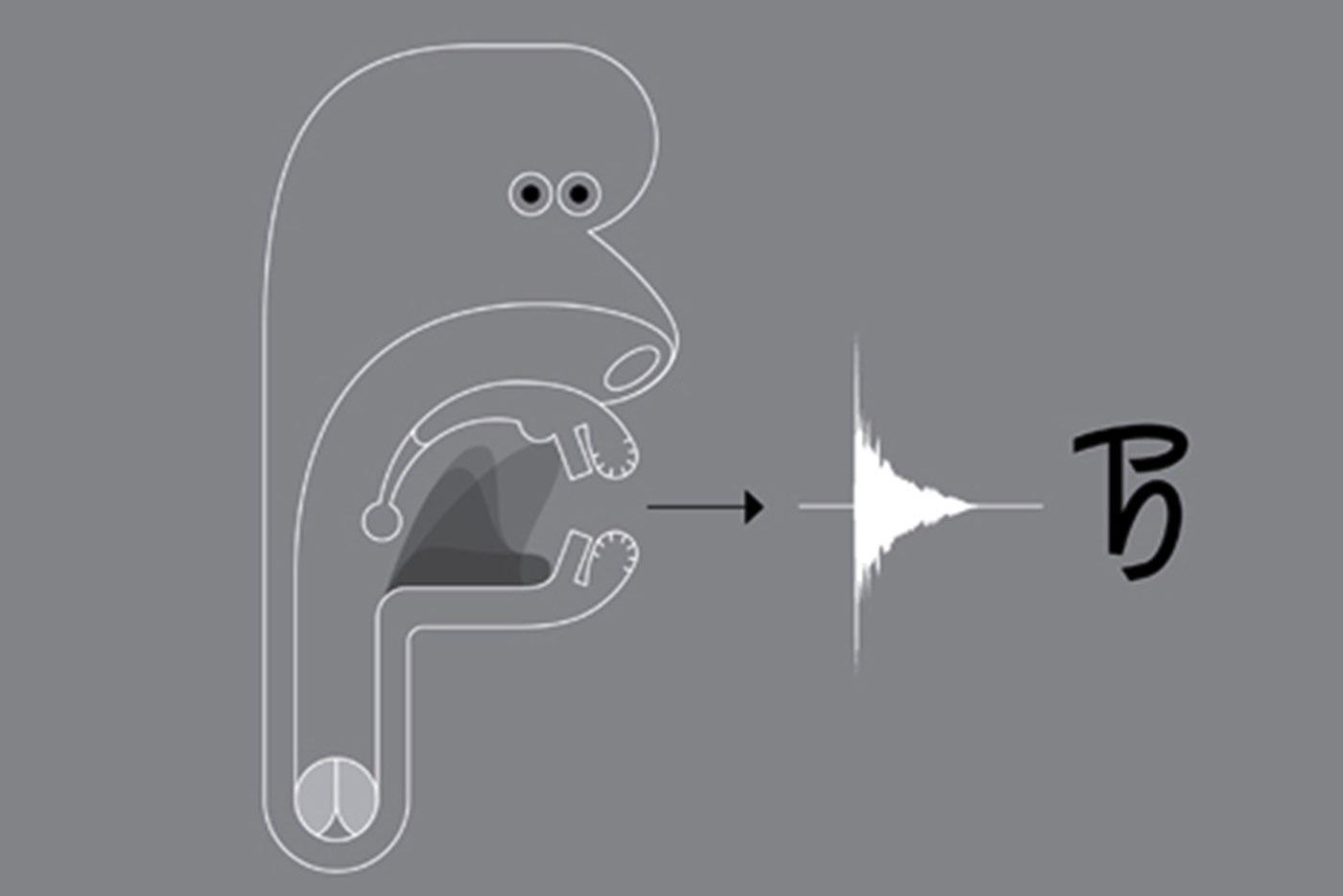

Human babies make a lot of noise to show that they actually exist. As ‘children are compelled from birth to utter sounds to communicate, they are posessed by no less primal urge – a desire to make a mark.’ Sounds like ‘mmmmmmm’ of ‘da da da da da da’ are easily modified into meaningful words like Mama and Dada. In the mouth and throat, raw sounds are transformed into the most elementary sounds of a language. Most speech sounds are lingual and are impossible to make without the tongue. For ‘this reason, we call a collection of communicative sounds a language, or even a tongue.’ Vowels and consonants are powerful tools to preserve to our thoughts.

‘The alphabet is one of the greatest inventions’ states Timothy Donaldson in the introduction of the book ‘Shapes and Sounds’. The Alphabet ‘has enabled the preservation and clear understanding of people’s thoughts, and it is simple to learn. It still has great significance; while the advent of type — printed alphabets — has curtailed any real development of the shapes of letters, the alphabet has been more greatly utilised in the last 500 years than ever before. Typography is the engine of graphic design, and writing is the fuel. But more than that, the alphabet has been the enabler of mass communication technologies from Morse code to the internet.’

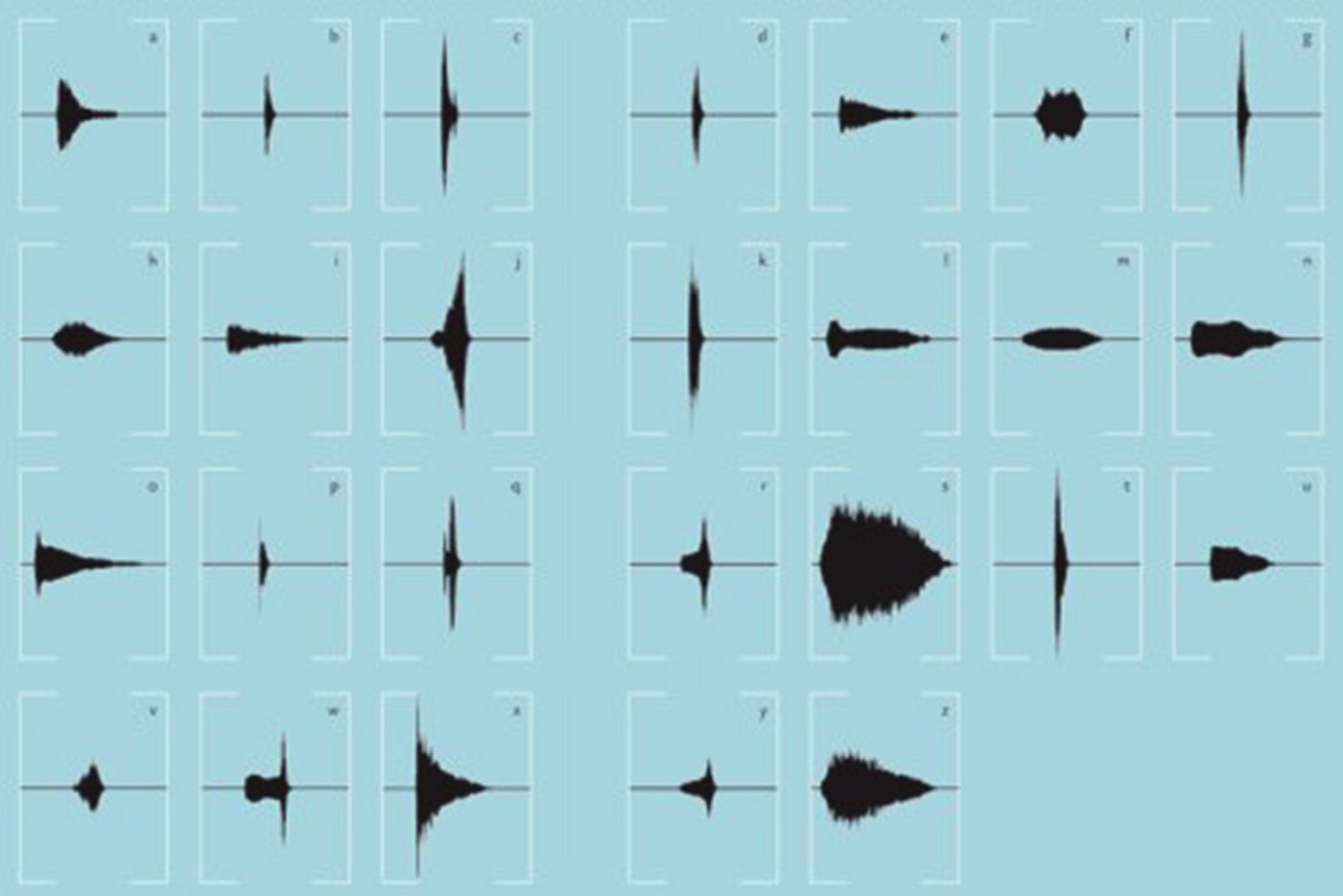

Donaldson puts the Latin alfabet into a broader context and indicates that it might have looked completely different. He makes his point with a lot of pictures and even more words. Donaldson elaborates on how the alphabet has happened. ‘Initially, there is a Token stage; objects that are smaller than the things they represent are used to make a record. Then there is a Pictographic stage: the small objects are simplified to pictures. Then a Logographic stage: the pictures are used to represent only the sounds made by the words. Finally, a Phonographic stage: words and syllables are are reduced to their component sounds, phonemes, and pictures to represent sounds.’ What the alphabets have in common is the idea that shapes represent sounds.

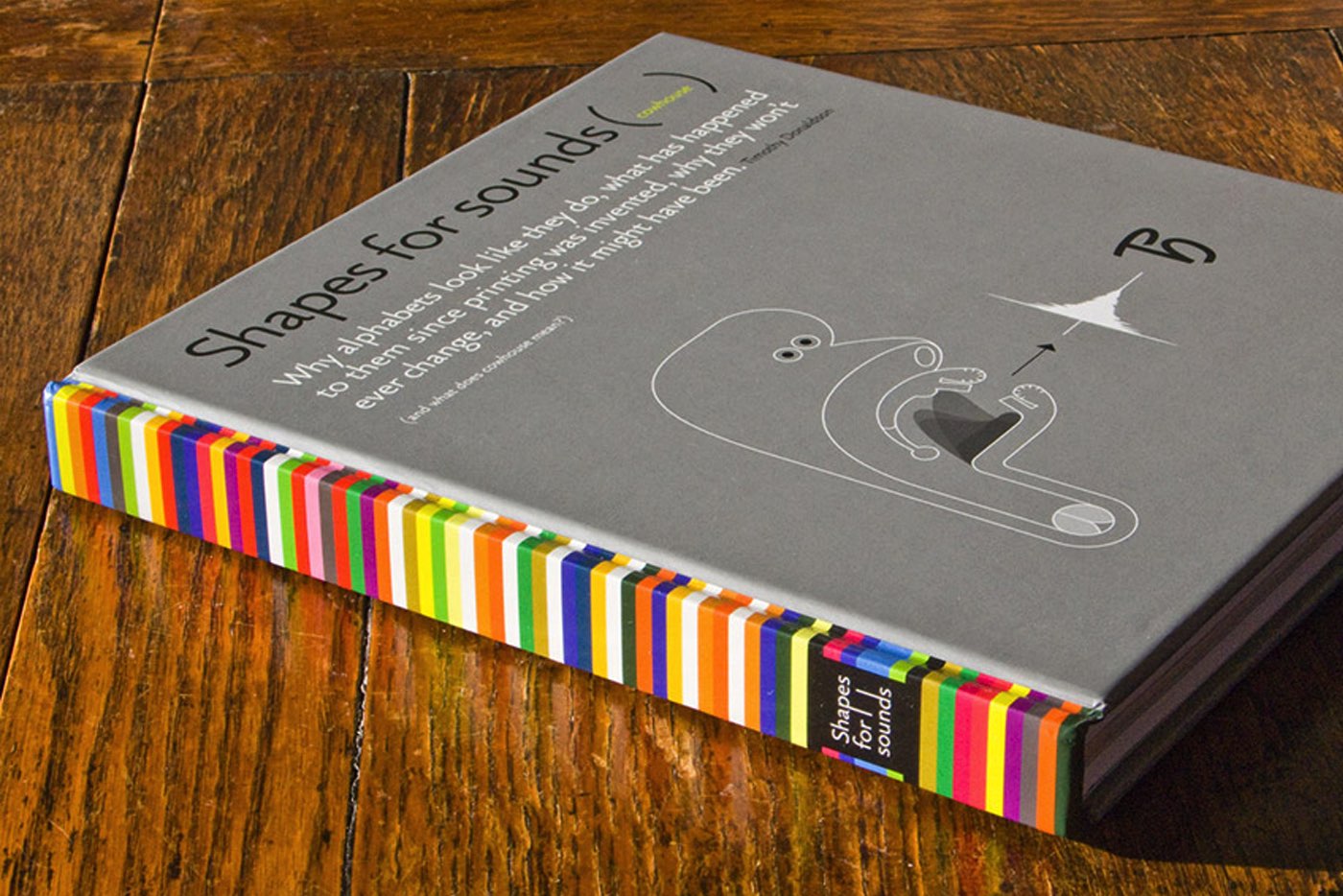

‘Shapes for Sounds’ is written for students of typography. In a vivid manner, the book it makes very dry study material digestible. The disciplines of design, typography, phonetics, linguistics and psychology are connected by the means of the radio alphabet in a chapter on sound. The spine of the book is patterned with a range of colours. It is up to the reader to decode the colour alphabet. The publication is eye candy for letter enthusiasts and contains sufficient references for those who want to broaden their knowledge on phonology or writing systems.

The book ‘Shapes for Sounds’ is available in the Alphabetum in The Hague. Shapes for Sounds: Why alphabets look like they do, what has happened to them since printing was invented, why they won’t ever change, and how it might have been. Timothy Donaldson. Mark Batty Publisher, 2008

Text: Marienelle Andringa

Human babies make a lot of noise to show that they actually exist. As ‘children are compelled from birth to utter sounds to communicate, they are posessed by no less primal urge – a desire to make a mark.’ Sounds like ‘mmmmmmm’ of ‘da da da da da da’ are easily modified into meaningful words like Mama and Dada. In the mouth and throat, raw sounds are transformed into the most elementary sounds of a language. Most speech sounds are lingual and are impossible to make without the tongue. For ‘this reason, we call a collection of communicative sounds a language, or even a tongue.’ Vowels and consonants are powerful tools to preserve to our thoughts.

‘The alphabet is one of the greatest inventions’ states Timothy Donaldson in the introduction of the book ‘Shapes and Sounds’. The Alphabet ‘has enabled the preservation and clear understanding of people’s thoughts, and it is simple to learn. It still has great significance; while the advent of type — printed alphabets — has curtailed any real development of the shapes of letters, the alphabet has been more greatly utilised in the last 500 years than ever before. Typography is the engine of graphic design, and writing is the fuel. But more than that, the alphabet has been the enabler of mass communication technologies from Morse code to the internet.’

Donaldson puts the Latin alfabet into a broader context and indicates that it might have looked completely different. He makes his point with a lot of pictures and even more words. Donaldson elaborates on how the alphabet has happened. ‘Initially, there is a Token stage; objects that are smaller than the things they represent are used to make a record. Then there is a Pictographic stage: the small objects are simplified to pictures. Then a Logographic stage: the pictures are used to represent only the sounds made by the words. Finally, a Phonographic stage: words and syllables are are reduced to their component sounds, phonemes, and pictures to represent sounds.’ What the alphabets have in common is the idea that shapes represent sounds.

‘Shapes for Sounds’ is written for students of typography. In a vivid manner, the book it makes very dry study material digestible. The disciplines of design, typography, phonetics, linguistics and psychology are connected by the means of the radio alphabet in a chapter on sound. The spine of the book is patterned with a range of colours. It is up to the reader to decode the colour alphabet. The publication is eye candy for letter enthusiasts and contains sufficient references for those who want to broaden their knowledge on phonology or writing systems.

The book ‘Shapes for Sounds’ is available in the Alphabetum in The Hague. Shapes for Sounds: Why alphabets look like they do, what has happened to them since printing was invented, why they won’t ever change, and how it might have been. Timothy Donaldson. Mark Batty Publisher, 2008

Text: Marienelle Andringa

previous

previous next

next